Intro to Discrete Math: How to Logically Prove Arguments

Proving arguments using logic is a key concept in discrete math and computer science.

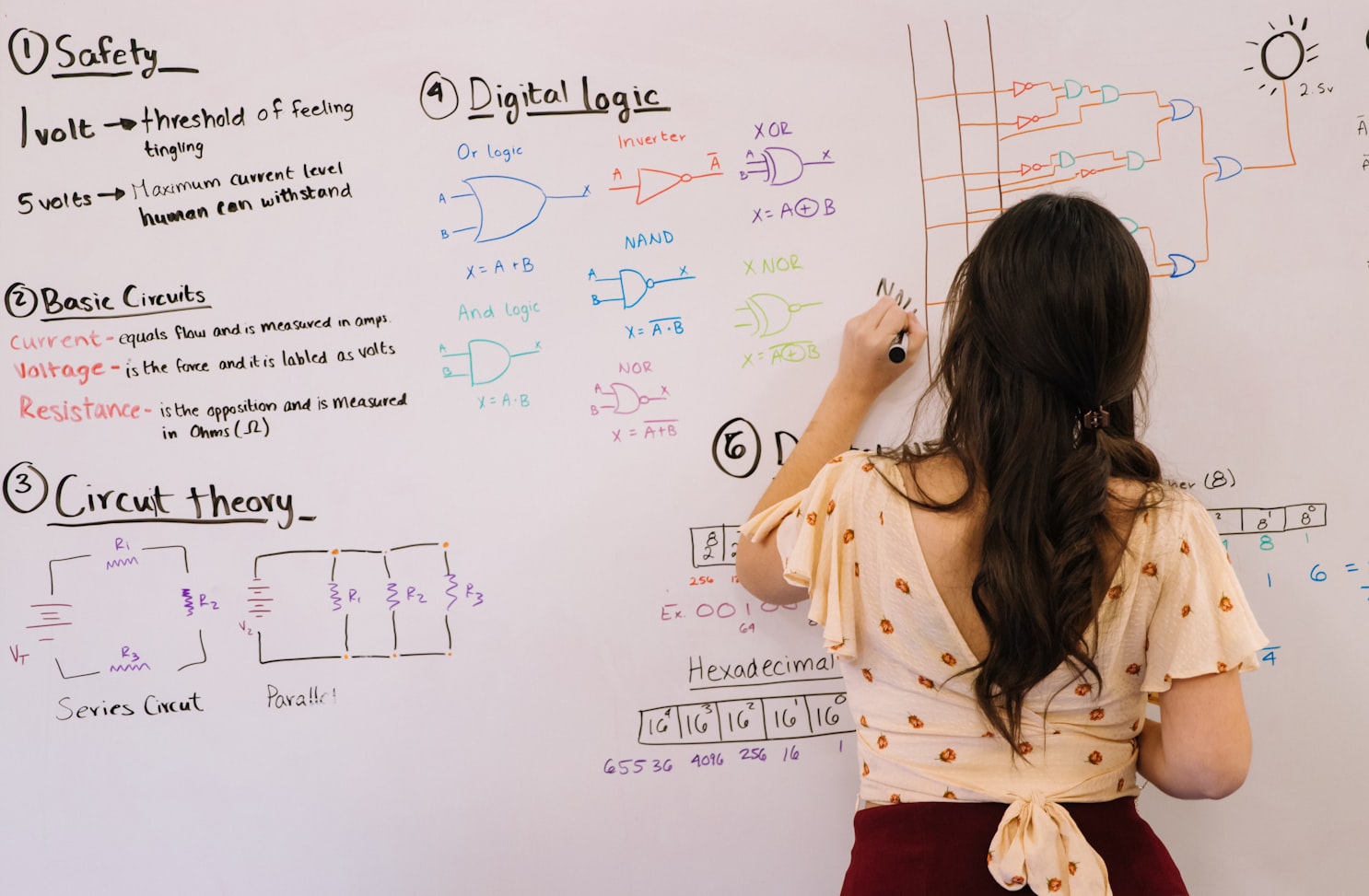

Photo by Randy Fath on Unsplash

Disclosure: When you purchase through links on my site, I may earn an affiliate commission. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Read the full disclosure

In this article, we explore the basics of logic in discrete mathematics, covering propositional variables, logical connectives/operators, truth tables, tautologies, contradictions, logical equivalence, and forming inverses, converses, and contrapositives of base implications. By understanding these concepts, you can build a strong foundation for further study in discrete math and its applications in computer science.

Introduction

This article is part of a series called "Log Base Two", a series dedicated to the relationship between math and computer science.

Just to give a bit of background on my experience in math, I've excelled in a total of 10 college courses in math:

Single-variable differential calculus

Single-variable integral calculus

Multi-variable differential and integral calculus

Multi-variable differential and integral calculus of vector-valued functions

Linear Algebra

Differential equations

Probability and statistics

Data analysis using R programming language

Multivariate statistics

Discrete math

For a large majority of those 10 classes, I ended up with A's.

Although, before college, I struggled a lot with math in the classroom, even though math had always been my favorite subject since I was in elementary school. I found it hard to truly grasp the concepts taught because my high school teachers were too focused on skill assessment. Instead of focusing on the actual concept being taught, I was too worried about how I was going to pass the test the following week.

Once I got to college, I realized that your math grade (or any grade for that matter) truly doesn't define your potential. Further, I'd argue that your success in math education is heavily influenced by the quality of the teacher/professor's teaching.

My mission with this series is to show other people that math isn't so scary if you break down mathematical concepts into digestible bouts of information and investigate use cases of math in your primary field of interest (in this case, computer science). Along the way, I hope to also supplement your math education with quality content. I believe that everyone is capable of learning and truly loving mathematics.

New articles in this series are posted every Thursday!

Amazon Prime Free Trial

Free 30-day trial for Amazon Prime: https://amzn.to/3RJN4zV

For college students; Free 6-month trial for Amazon Prime Student: https://amzn.to/45mPuHV

I. Overview of logic

Our ability to reason using logic is perhaps one of the most defining qualities of what makes us human.

Even when we're being "overly emotional", we're technically still using logic. Albeit, this type of logic is usually based on fallacies.

For instance, if you choose to never visit a restaurant again because you got food poisoning from it once, you're using logic based on your personal experience of the painful torment you had to endure that will forever be tied to that restaurant in your mind.

Alternatively, if you got food poisoning from a restaurant once but choose to keep dining at the restaurant, maybe your logical defense is that you've eaten at the restaurant hundreds of times so that one time is not statistically significant.

In both of those cases of reasoning, you're forming an argument constructed from a logical relationship between 2 propositions.

In the first case, your root, refined argument is: "If I get food poisoning from a restaurant, then I'll get food poisoning from the restaurant again." The first proposition is "If I get food poisoning from a restaurant", and the second proposition is "I'll get food poisoning from the restaurant again". You then logically construct your argument by connecting these 2 propositions with an "if...then" statement. Whether this argument is true or not is another story.

In the second case, your root, refined argument is: "If I get food poisoning from a restaurant less than 1% of the hundreds of times I've eaten there, then it is due to random chance." The first proposition is "If I get food poisoning from a restaurant less than 1% of the hundreds of times I've eaten there", and the second proposition is "It is due to random chance". Once again, you connect these 2 propositions using an "if...then" statement to form your argument.

At this point, it should be noted that sometimes, certain arguments can be incredibly hard to prove or disprove, and sometimes even impossible to prove or disprove.

For the first argument to be true, all that has to happen is you get food poisoning from the restaurant at least once more. Theoretically, you could get food poisoning from the restaurant again the very next month and conclusively prove your argument true. Alternatively, for the first argument to be false, you'd have to never get food poisoning from the restaurant again in your life. Although, assuming you live for a long time, it could take decades before this argument can conclusively be proven false.

On the other hand, the second argument is very hard to prove true or false from the get-go. This is because even if you never get food poisoning again from that restaurant, you can't definitively say that that one time was due to pure random chance. Perhaps you were unknowingly on a date with the chef's ex-significant other at the restaurant, and the jealous chef purposely spoiled your food.

While it may seem like I'm being unrealistic and overly cynical about this whole story above, there are even some cases in "pure" math where a particular argument can simply never be proven or disproven.

One of my favorite mathematicians of all time, Kurt Gödel, proved his "incompleteness theorems" showing that there can exist statements about/within a formal system that can't be proven or disproven and that the formal system itself can not prove that its own rules are logically consistent.

For instance, our second argument in our story about food poisoning might be true based on statistical inference, but as I stated, this doesn't mean that it can be proven true. Essentially, that argument is only as true as the statistical inference you're making, and that inference itself is based on conditions/rules that can't be proven to be logically consistent.

Now that you're mind is blown, let's break down the components of arguments and logical reasoning.

a) Propositional variables

In discrete math, we typically represent propositions as variables for convenience.

Usually, the standard variables used for an argument with 2 propositions are P and Q.

For example, for the first argument in our food poisoning story, we'd define the propositions as:

$$P: If \ I \ get \ food \ poisoning \ from \ a \ restaurant$$

$$Q: I'll \ get \ food \ poisoning \ again$$

b) Logical operations and connectives

The 5 rudimentary connectives/operators in propositional logic are:

- Implication (if...then)

$$P \Rightarrow Q$$

- Bidirectional (if, and only if,...)

$$P \Leftrightarrow Q$$

- Conjunction (and)

$$P \land Q$$

- Disjunction (or)

$$P \lor Q$$

- Negation (not)

$$\lnot P$$

c) Truth tables

To systematically and conveniently show that an argument is true, we use truth tables.

In a truth table, you essentially consider every possible case of an argument to logically show whether an argument is true or false.

For an argument with 2 propositions, there are 4 unique cases: both propositions are true, both propositions are false, only the first proposition is true, and only the second proposition is true.

Let's write out the basic truth tables for all 5 of those rudimentary connectives/operators.

Implication

| P | Q | P --> Q |

| True | True | True |

| True | False | False |

| False | True | True |

| False | False | True |

As we see for an argument involving 2 propositions, an implication is only false when the first proposition is true but the second proposition is false.

Intuitively, this makes sense.

For instance, consider the following implication:

$$P: x = 2$$

$$Q: 3x = 5$$

$$P \Rightarrow Q$$

In this case, if P is taken as true, then we can assume that Q is false (since if x = 2, then 3x would equal 6). Therefore, our implication itself "If x = 2, then 3x = 5" is false.

One implication truth-value that might not make sense right away is how the implication "if P is false, then Q is true" is a true implication.

Consider the following implication:

$$P: It's \ always \ sunny \ outside$$

$$Q: The \ sun \ is \ always \ shining \ onto \ Earth$$

$$P \Rightarrow Q$$

Since there are sometimes clouds in the atmosphere, we can take P as sometimes false. Although, since the Earth is always in the path of the sun's light, we can take Q as always true. However, the implication itself "If it's always sunny outside, then the sun is always shining onto Earth" is true.

Bidirectional

To construct our bidirectional truth table, let's first think about what a bidirectional argument means in the context of implication.

In a bidirectional argument, we're essentially making an implication that works both ways.

Therefore, let's construct our bidirectional truth table with this in mind by making a column for "if Q, then P".

| P | Q | P --> Q | Q --> P | P <--> Q |

| True | True | True | True | True |

| True | False | False | True | False |

| False | True | True | False | False |

| False | False | True | True | True |

As we see for an argument involving 2 propositions, a bidirectional argument is only true when P and Q are logically equivalent (they have the same truth-vaues). So either P and Q are both true, or they're both false.

Consider the following bidirectional argument:

$$P: Penguins \ can \ fly$$

$$Q: All \ birds \ can \ fly$$

$$P \Leftrightarrow Q$$

Our argument is "Penguins can fly if, and only if, all birds can fly". As you may already know, penguins can't fly, therefore not all birds can fly (so both propositions are false). Although, the bidirectional argument itself "Penguins can fly if, and only if, all birds can fly" is true.

Conjunction

The other 3 connectives/operators are relatively straightforward.

Also, as a side note, these remaining 3 connectives/operators don't form complete arguments on their own but rather are used as components of an argument.

The conjunction of 2 propositions forms the statement "P and Q".

In terms of truth-value, a conjunction of 2 propositions is true if, and only if, both propositions are true. Therefore, if at least 1 of the propositions is false, then the conjunction is false.

| P | Q | P & Q |

| True | True | True |

| True | False | False |

| False | True | False |

| False | False | False |

Consider the following conjunction:

$$P: Monday \ comes \ before \ Tuesday$$

$$Q: Tuesday \ comes \ after \ Monday$$

$$P \land Q$$

Since both propositions are true on their own, the conjunction "Monday comes before Tuesday and Tuesday comes after Monday" is true.

Disjunction

The disjunction of 2 propositions forms the statement "P or Q".

In terms of truth-value, if at least 1 of the propositions is true, then the disjunction is true. Therefore, a disjunction of 2 propositions is false if, and only if, both of the propositions are false.

| P | Q | P or Q |

| True | True | True |

| True | False | True |

| False | True | True |

| False | False | False |

Consider the following disjunction:

$$P: I'm \ always \ right$$

$$Q: I'm \ sometime's \ wrong$$

$$P \lor Q$$

The first proposition is false, but the second proposition is true. Therefore, the disjunction "I'm always right or I'm sometimes wrong" is true.

Negation

The last logical operator we'll go over is negation.

Negation can operate on entire arguments, statements involving conjunctions or disjunctions, and even propositions themselves.

The negation of a proposition, argument, or statement is simply the opposite truth-value.

This means that if a proposition is true, then its negation is false. Alternatively, if a proposition is false, then its negation is true.

| P | ! P |

| True | False |

| False | True |

Consider the following negation:

$$P: Our \ solar \ system \ has \ 1 \ star$$

$$\lnot P$$

The proposition is true, therefore the negation "Our solar system does not have 1 star" is false.

d) Tautologies

A tautology is a logical statement or argument that is shown to always be true regardless of the truth values of the proposition(s).

There are plenty of examples of tautologies, but let's consider a simple tautology that involves only 1 proposition.

Using the operators we've covered, how do you think we might be able to form a tautology with only 1 proposition?

Since negation is the only operator that can be used on 1 proposition value, let's start with a negation truth table.

| P | ! P |

| True | False |

| False | True |

Since the negation is always the opposite value of the proposition, it'd be wise to next form a disjunction between P and ! P.

| P | ! P | P or ! P |

| True | False | True |

| False | True | True |

And voilà, we have a tautology:

$$P \lor \lnot P$$

Consider the following proposition:

$$P: I'm \ a \ billionaire$$

As an English statement, we have "I'm a billionaire or I'm not a billionaire". Logically, regardless of the truth value of the proposition, that statement is always true.

Let's now think of a tautology involving 2 propositions.

As we saw when we covered those 5 operators/connectives, the only 2 connectives that form logical statements that are true most of the time are implications and disjunctions (both of these connectives between two propositions result in a statement that is true 75% of the time).

Since we used a disjunction in the last example, let's try using an implication.

| P | Q | P --> Q |

| True | True | True |

| True | False | False |

| False | True | True |

| False | False | True |

That second implication case would be true if we had used a bidirectional connective instead of implication so let's include a bidirectional connective now.

| P | Q | P --> Q | (P --> Q) <--> Q |

| True | True | True | True |

| True | False | False | True |

| False | True | True | True |

| False | False | True | False |

Now that the second case is true, the fourth case is false. Let's target that last case with a disjunction and negation.

| P | Q | P --> Q | (P --> Q) <--> Q | (P --> Q) <--> (Q or ! P) |

| True | True | True | True | True |

| True | False | False | True | True |

| False | True | True | True | True |

| False | False | True | False | True |

And there you have it! We formed a tautology involving 2 propositions:

$$(P \Rightarrow Q) \Leftrightarrow (Q \lor \lnot P)$$

Consider the following propositions:

$$P: Pigs \ can \ fly$$

$$Q: Pigs \ are \ faster \ than \ airplanes$$

As an English statement, our tautology is "If pigs can fly, then pigs are faster than airplanes if, and only if, pigs are faster than airplanes or pigs can't fly". Regardless of whether those propositions are true or false on their own, that statement is always logically true.

As you can see, part of the fun of tautologies is that you can form completely absurd arguments that are always logically true.

e) Contradictions

Contrary to tautologies, we have contradictions. Contradictions are logical statements or arguments that are shown to always be false regardless of the truth-values of the propositions.

Similar to when we considered a tautology with only 1 proposition, let's try the same thing with a contradiction.

Let's start with just a simple negation again.

| P | ! P |

| True | False |

| False | True |

Since the negation of a proposition is always the opposite truth-value of the proposition, we can use a conjunction of the proposition and the proposition's negation.

| P | ! P | P & ! P |

| True | False | False |

| False | True | False |

And we now have our contradiction:

$$P \land \lnot P$$

Consider the following proposition:

$$P: I \ work \ for \ N.A.S.A.$$

We can then form the contradiction "I work for N.A.S.A. and I don't work for N.A.S.A.". Regardless of whether I work for N.A.S.A., this is a statement that is always logically false since both can't be true at the same time.

Let's now try forming a contradiction involving 2 propositions.

Since a conjunction of two propositions is only true 25% of the time, let's start with a conjunction of the first proposition and the second proposition's negation.

| P | Q | P & ! Q |

| True | True | False |

| True | False | True |

| False | True | False |

| False | False | False |

The only case that prevents our statement from being a contradiction is when the first proposition is true and the second proposition is false. If you remember, the truth-values of an implication between 2 propositions lead to the exact opposite results where the second case is the only case that's false and the rest of the cases are true. Because of this, we've found an important result: the negation of an implication between two propositions is logically equivalent to the conjunction of the first proposition with the second proposition's negation.

In math symbols:

$$\lnot (P \Rightarrow Q) \equiv (P \land \lnot Q)$$

As a side note, that symbol that looks like an equals sign with a third line is called a "logical equivalence" symbol.

Back to our contradiction, let's now add a disjunction between the first statement and the first proposition.

| P | Q | P & ! Q | (P & ! Q) or P |

| True | True | False | True |

| True | False | True | True |

| False | True | False | False |

| False | False | False | False |

If you notice, the truth values of our statement are logically equivalent to the first proposition's truth values.

$$(P \land \lnot Q) \lor P \equiv P$$

Using this fact, let's now form a conjunction between the statement we have and the negation of the first proposition.

| P | Q | P & ! Q | (P & ! Q) or P | ((P & ! Q) or P) & ! P |

| True | True | False | True | False |

| True | False | True | True | False |

| False | True | False | False | False |

| False | False | False | False | False |

We've now arrived at a contradiction involving two propositions.

$$((P \land \lnot Q) \lor P) \land \lnot P$$

Consider the following propositions:

$$P: I \ live \ on \ Earth$$

$$Q: I'm \ a \ human$$

We can then form the contradiction "I live on Earth and I'm not a human, or I live on Earth. Also, I don't live on Earth". Regardless of whether these propositions are true, this statement will always be logically false.

f) Logical equivalence

I briefly went over logical equivalence in the last section. Remember, if a statement/proposition has an identical truth table to another statement/proposition, then they are logically equivalent.

Although, this is not the only way to show logical equivalence.

Another method to show logical equivalence between two statements/propositions is if the bidirectional argument between them is a tautology.

Remember the tautology we made earlier?

$$(P \Rightarrow Q) \Leftrightarrow (Q \lor \lnot P)$$

Since this statement is both a tautology and a bidirectional argument between two substatements, the two substatements are logically equivalent.

In math symbols:

$$(P \Rightarrow Q) \equiv (Q \lor \lnot P)$$

Let's also review the example propositions we used:

$$P: Pigs \ can \ fly$$

$$Q: Pigs \ are \ faster \ than \ airplanes$$

The statement "If pigs can fly, then pigs are faster than airplanes" is logically equivalent to the statement "Pigs can't fly or pigs are faster than airplanes".

g) Inverse, converse, and contrapositive

For statements that are implications, we can form the inverse, converse, and contrapositive of that implication.

Let's start by defining our base implication:

$$P \Rightarrow Q$$

The inverse is then defined as:

$$\lnot P \Rightarrow \lnot Q$$

So if our base implication is the statement "If I study, then I'll do well on the test", then the inverse is the statement "If I don't study, then I won't do well on the test".

Let's analyze the truth table for these statements.

| P | Q | P --> Q | ! P --> ! Q |

| True | True | True | True |

| True | False | False | True |

| False | True | True | False |

| False | False | True | True |

Notice how if the inverse is false, then the base implication is true. This fact will come in handy when you prove math theorems.

Let's say you don't study for your test, yet you do well on the test. Then, you've disproven the inverse statement "If I don't study, then I won't do well on the test". By disproving that statement, you've automatically also proven the statement "If I study, then I'll do well on the test". Intuitively, this makes sense, as we're essentially saying that if we did well on the test without studying, then we would have for sure done well if we had studied.

Next, let's go over the converse.

The converse of our base implication is defined as:

$$Q \Rightarrow P$$

So if our base implication is "If I study, then I'll do well on the test", then the converse is "If I do well on the test, then I had studied".

Let's analyze the truth table.

| P | Q | P --> Q | Q --> P |

| True | True | True | True |

| True | False | False | True |

| False | True | True | False |

| False | False | True | True |

If you notice, the truth table for the converse is the same as the truth table for the inverse, thus we've just shown that the inverse is logically equivalent to the converse.

$$(\lnot P \Rightarrow \lnot Q) \equiv (Q \Rightarrow P)$$

This also means that by proving the converse false, we consequently prove the base implication true. Once again, this fact will come in handy when you need to prove a math theorem.

Finally, let's cover the contrapositive.

The contrapositive of our base implication is defined as:

$$\lnot Q \Rightarrow \lnot P$$

So if our base implication is "If I study, then I'll do well on the test", then our contrapositive is "If I don't do well on the test, then I hadn't studied".

| P | Q | P --> Q | ! Q --> ! P |

| True | True | True | True |

| True | False | False | False |

| False | True | True | True |

| False | False | True | True |

If you notice, the truth values for the contrapositive are the same as the base implication, thus the contrapositive is logically equivalent to the base implication.

$$(P \Rightarrow Q) \equiv (\lnot Q \Rightarrow \lnot P)$$

This means that if we prove the contrapositive to be true, then we consequently prove the base implication to be true.

So if you don't do well on the test and you hadn't studied for it, then you've proven the statement "If I don't do well on the test, then I hadn't studied" to be true. Consequently, you've also proven the statement "If I study, then I'll do well on the test" to be true.

III. Conclusion

I hope that this article has served as a starting ground for understanding the intricacies around logical statements in discrete math.

In this article, you learned about propositional variables, logical connectives/operators, truth tables, tautologies, contradictions, logical equivalence, and forming inverses, converses, and contrapositives of base implications.

The next topic to learn about in discrete math is how to apply everything you learned in this article to prove mathematical theorems. This might be a topic I cover in the future, so stay tuned ;)

If you have any lingering questions, then please make sure to leave a comment down below.

Lastly, make sure to follow my newsletter to never miss out on when I post new content!